mirror of

https://github.com/Dummi26/mers.git

synced 2026-01-07 12:50:39 +01:00

Merge branch 'main' of https://www.github.com/Dummi26/mers

This commit is contained in:

288

mers/README.md

288

mers/README.md

@@ -1,138 +1,228 @@

|

|||||||

# mers

|

# mers

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

Mers is a high-level programming language.

|

|

||||||

It is designed to be safe (it doesn't crash at runtime) and as simple as possible.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

Install from *crates.io*:

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

```sh

|

```sh

|

||||||

cargo install mers

|

cargo install mers

|

||||||

```

|

```

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

## what makes it special

|

Mers is a simple, safe programming language.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

### Simplicity

|

## features

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

Mers is simple. There are only a few expressions:

|

- mers' syntax is simple and concise

|

||||||

|

- mers is type-checked, but behaves almost like a dynamically typed language

|

||||||

|

- it has no nulls or exceptions

|

||||||

|

- references in mers are explicit: `&var` vs. just `var`

|

||||||

|

- no `goto`s (or `break`s or `return`s)

|

||||||

|

- locking (useful for multithreading, any reference can be locked)

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

- Values (`1`, `-2.4`, `"my string"`)

|

# examples

|

||||||

- Blocks (`{ statement1, statement2 }` - comma is optional, newline preferred)

|

|

||||||

- Tuples (`(5, 2)`) and Objects (`{ x: 5, y: 2 }`)

|

|

||||||

- Variable initializations (`:=`)

|

|

||||||

- Assignments (`=`)

|

|

||||||

- Variables: `my_var`, `&my_var`

|

|

||||||

- If statements: `if <condition> <then> [else <else>]`

|

|

||||||

- Functions: `arg -> <do something>`

|

|

||||||

- Function calls: `arg.function`

|

|

||||||

+ or `arg1.function(arg2, arg3)` (nicer syntax for `(arg1, arg2, arg3).function`)

|

|

||||||

- Type annotations: `[Int] (1, 2, 3).sum`

|

|

||||||

+ Type definitions: `[[MyType] Int]`, `[[TypeOfMyVar] := my_var]`

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

Everything else is implemented as a function.

|

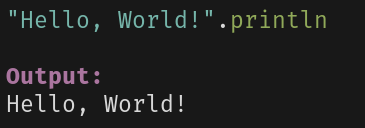

## Hello, World!

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

### Types and Safety

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

Mers is built around a type-system where a value could be one of multiple types.

|

In mers, `.function` is the syntax used to call functions.

|

||||||

|

Everything before the `.` is the function's argument.

|

||||||

|

In this case, our argument is the string containing *Hello, World!*,

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

```

|

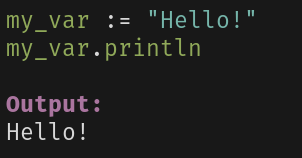

## Variables

|

||||||

x := if condition { 12 } else { "something went wrong" }

|

|

||||||

```

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

In mers, the compiler tracks all the types in your program,

|

|

||||||

and it will catch every possible crash before the program even runs:

|

|

||||||

If we tried to use `x` as an int, the compiler would complain since it might be a string, so this **does not compile**:

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

```

|

We use `name := value` to declare a variable, in this case `my_var`.

|

||||||

list := (1, 2, if true 3 else "not an int")

|

We can then simply write `my_var` whenever we want to use its value.

|

||||||

list.sum.println

|

|

||||||

```

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

Type-safety for functions is different from what you might expect.

|

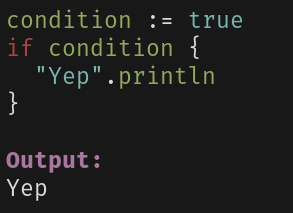

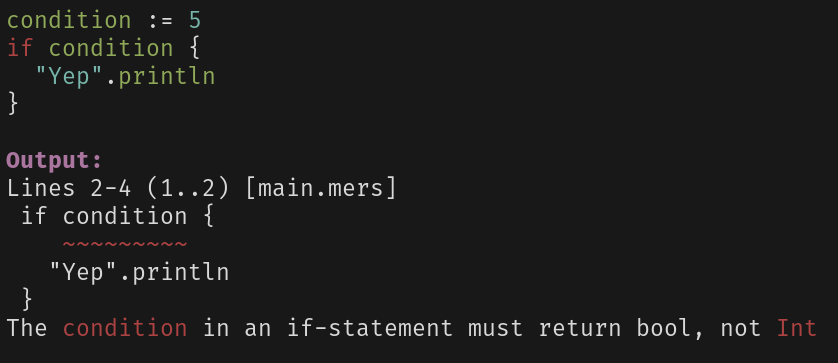

## If

|

||||||

You don't need to tell mers what type your function's argument has - you just use it however you want as if mers was a dynamically typed language:

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

```

|

|

||||||

sum_doubled := iter -> {

|

|

||||||

one := iter.sum

|

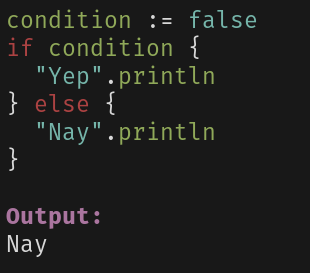

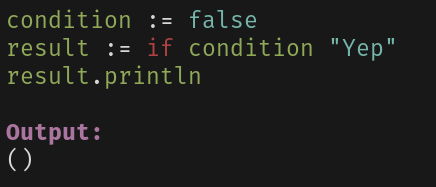

An `if` is used to conditionally execute code.

|

||||||

(one, one).sum

|

Obviously, since our condition is always `true`, our code will always run.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

The condition in an `if` has to be a bool, otherwise...

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## Else

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

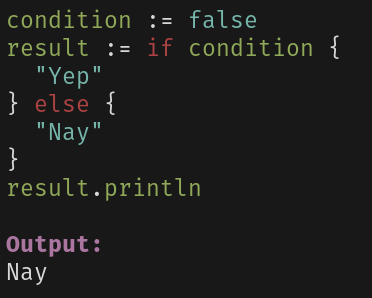

We can add `else` directly after an `if`. This is the code that will run if the condition was `false`.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## Using If-Else to produce a value

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Depending on the languages you're used to, you may want to write something like this:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

```js

|

||||||

|

var result

|

||||||

|

if (condition) {

|

||||||

|

result = "Yay"

|

||||||

|

} else {

|

||||||

|

result = "Nay"

|

||||||

}

|

}

|

||||||

(1, 2, 3).sum_doubled.println

|

|

||||||

```

|

```

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

We could try to use the function improperly by passing a string instead of an int:

|

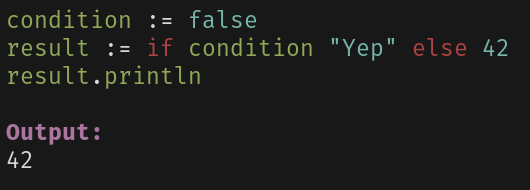

But in mers, an `if-else` can easily produce a value:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

```

|

|

||||||

(1, 2, "3").sum_doubled.println

|

|

||||||

|

We can shorten this even more by writing

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## What if the branches don't have the same type?

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Rust also allows us to return a value through `if-else` constructs, as long as they are of the same type:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

```rs

|

||||||

|

if true {

|

||||||

|

"Yep"

|

||||||

|

} else {

|

||||||

|

"Nay"

|

||||||

|

}

|

||||||

```

|

```

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

But mers will catch this and show an error, because the call to `sum` inside of `sum_doubled` would fail.

|

But as soon as we mix two different types, it no longer compiles:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

#### Type Annotations

|

```rs

|

||||||

|

if true {

|

||||||

Eventually, mers' type-checking will cause a situation where calling `f1` causes an error,

|

"Yep"

|

||||||

because it calls `f2`, which calls `f3`,

|

} else {

|

||||||

which tries to call `f4` or `f5`, but neither of these calls are type-safe,

|

5 // Error!

|

||||||

because, within `f4`, ..., and within `f5`, ..., and so on.

|

}

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

Error like this are basically unreadable, but they can happen.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

To prevent this, we should type-check our functions (at least the non-trivial ones) to make sure they do what we want them to do:

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

```

|

|

||||||

f1 := /* ... */

|

|

||||||

// Calling `f1` with an int should cause it to return a string.

|

|

||||||

// If `f1` can't be called with an int or it doesn't return a string, the compiler gives us an error here.

|

|

||||||

[(Int -> String)] f1

|

|

||||||

```

|

```

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

We can still try calling `f1` with non-int arguments, and it may still be type-safe and work perfectly fine.

|

In mers, this isn't an issue:

|

||||||

If you want to deny any non-int arguments, the type annotation has to be in `f1`'s declaration or you have to redeclare `f1`:

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

```

|

|

||||||

f1 := [(Int -> String)] /* ... */

|

|

||||||

// or

|

|

||||||

f1 := /* ... */

|

|

||||||

f1 := [(Int -> String)] f1

|

|

||||||

```

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

This hard-limits the type of `f1`, similar to what you would expect from functions in statically typed programming languages.

|

The variable `result` is simply assigned the type `String/Int`, so mers always knows that it has to be one of those two.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

However, even when using type annotations for functions, mers can be more dynamic than most other languages:

|

We can see this if we add a type annotation:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

```

|

|

||||||

f1 := [(Int/Float -> String, String -> ()/Float)] /* ... */

|

|

||||||

```

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

Here, `f1`'s return type depends on the argument's type: For numbers, `f1` returns a string, and for strings, `f1` returns an empty tuple or a float.

|

Obviously, the `if-else` doesn't always return an `Int`, which is why we get an error.

|

||||||

Of course, if `f1`'s implementation doesn't satisfy these requirements, we get an error.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

### Error Handling

|

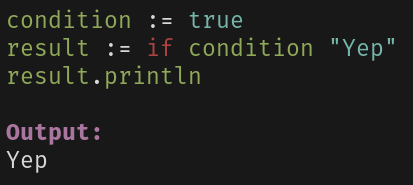

## Using If without Else to produce a value

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

Errors in mers are normal values.

|

If there is no `else` branch, mers obviously has to show an error:

|

||||||

For example, `("ls", ("/")).run_command` has the return type `({Int/Bool}, String, String)/RunCommandError`.

|

|

||||||

This means it either returns the result of the command (exit code, stdout, stderr) or an error (a value of type `RunCommandError`).

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

So, if we want to print the programs stdout, we could try

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

```

|

Or so you thought... But no, mers doesn't care. If the condition is false, it just falls back to an empty tuple `()`:

|

||||||

(s, stdout, stderr) := ("ls", ("/")).run_command

|

|

||||||

stdout.println

|

|

||||||

```

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

But if we encountered a `RunCommandError`, mers wouldn't be able to assign the value to `(s, stdout, stderr)`, so this doesn't compile.

|

|

||||||

Instead, we need to handle the error case, using the `try` function:

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

```

|

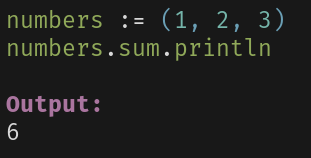

## Sum of numbers

|

||||||

("ls", ("/")).run_command.try((

|

|

||||||

(s, stdout, stderr) -> stdout.println,

|

|

||||||

error -> error.println,

|

|

||||||

))

|

|

||||||

```

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

For your own errors, you could use an object: `{err: { read_file_err: { path: /* ... */, reason: /* ... */ } } }`.

|

|

||||||

This makes it clear that the value represents an error and it is convenient when pattern-matching:

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

- `{ err: _ }`: all errors

|

## Sum of something else?

|

||||||

- `{ err: { read_file_err: _ } }`: only read-file errors

|

|

||||||

- `{ err: { parse_err: _ } }`: only parse errors

|

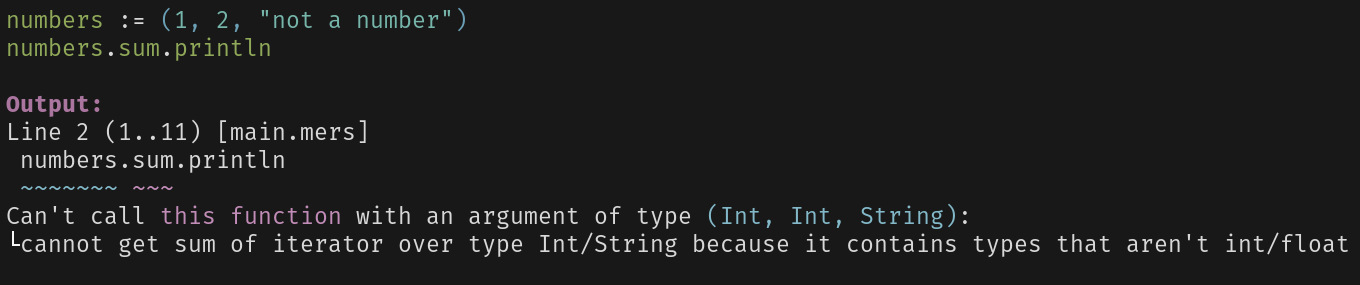

If not all of the elements in our `numbers` tuple are actually numbers, this won't work.

|

||||||

- `{ err: { read_file_err: { path: _, reason: { permission_denied: _ } } } }`: only read-file: permission-denied errors

|

Instead, we'll get a type-error:

|

||||||

- ...

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## Loops

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

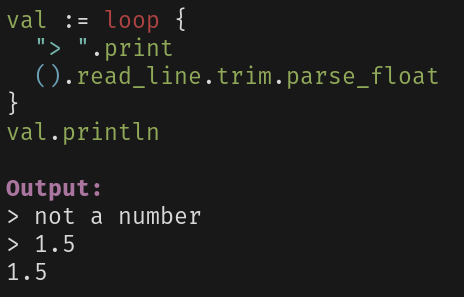

This program asks the user for a number. if they type a valid number, it prints that number.

|

||||||

|

If they don't type a valid number, they will be asked again.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

This works because `parse_float` returns `()/(Float)`, which happens to align with how loops in `mers` work:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

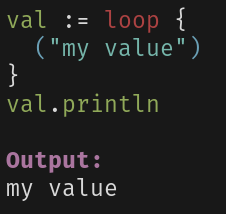

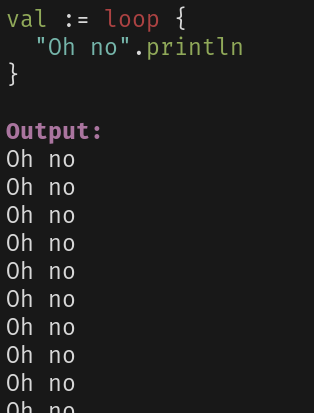

|

A `loop` will execute the code. If it is `()`, it will execute it again.

|

||||||

|

If it is `(v)`, the loop stops and returns `v`:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

With this, we can loop forever:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

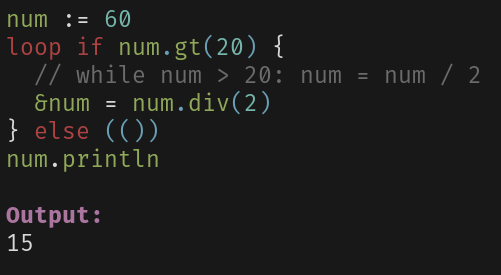

|

We can implement a while loop:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Or a for loop:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

The `else (())` tells mers to exit the loop and return `()` once the condition returns `false`.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## Functions

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

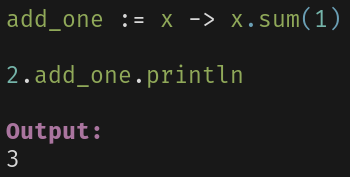

|

Functions are expressed as `arg -> something`, where `arg` is the function's argument and `something` is what the function should do.

|

||||||

|

It's usually convenient to assign the function to a variable so we can easily use it:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

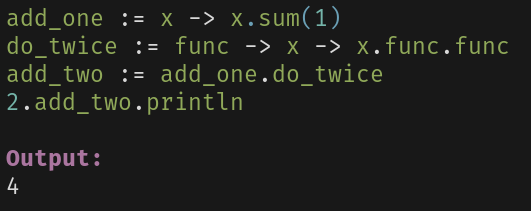

Since functions are just normal values, we can pass them to other functions, and we can return them from other functions:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Here, `do_twice` is a function which, given a function, returns a new function which executes the original function twice.

|

||||||

|

So, `add_one.do_twice` becomes a new function which could have been written as `x -> x.add_one.add_one`.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

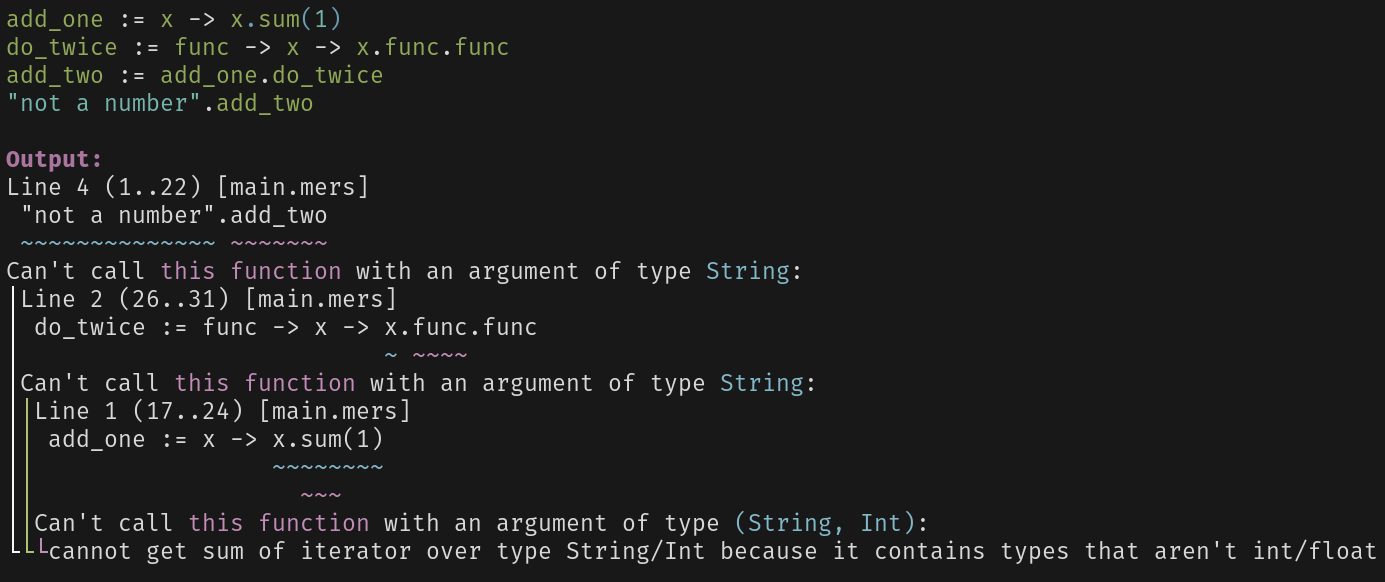

Of course, this doesn't compromise type-safety at all:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Mers tells us that we can't call `add_two` with a `String`,

|

||||||

|

because that would call the `func` defined in `do_twice` with that `String`, and that `func` is `add_one`,

|

||||||

|

which would then call `sum` with that `String` and an `Int`, which doesn't work.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

The error may be a bit long, but it tells us what went wrong.

|

||||||

|

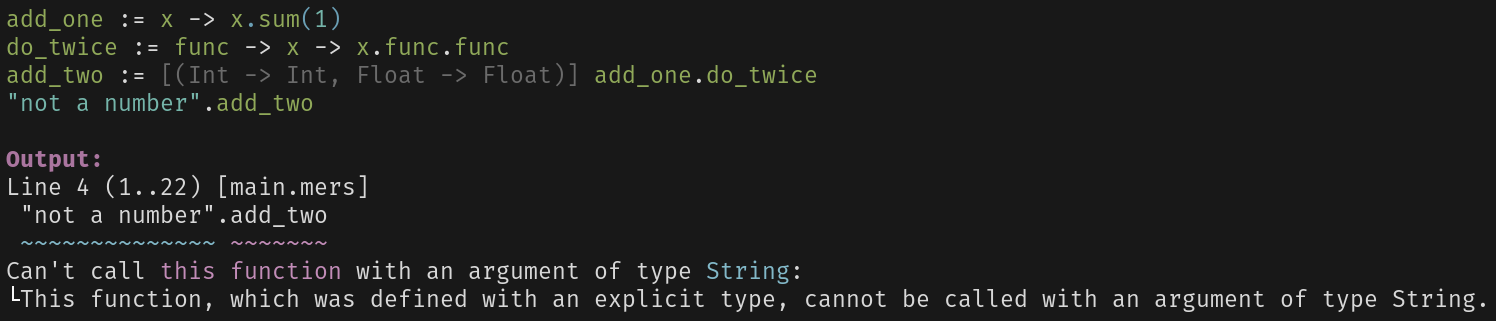

We could make it a bit more obvious by adding some type annotations to our functions:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## Advanced variables

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

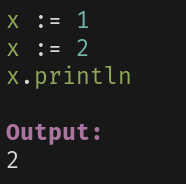

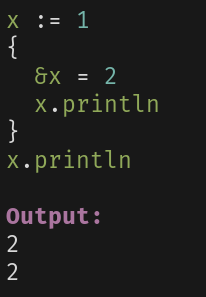

In mers, we can declare two variables with the same name:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

As long as the second variable is in scope, we can't access the first one anymore, because they have the same name.

|

||||||

|

This is not the same as assigning a new value to x:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

The second `x` only exists inside the scope created by the code block (`{`), so, after it ends (`}`), `x` refers to the original variable again, whose value was not changed.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

To assign a new value to the original x, we have to write `&x =`:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## References

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

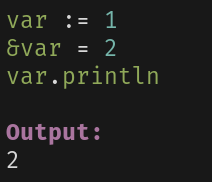

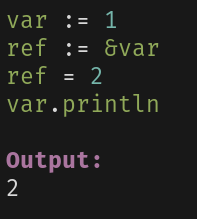

|

Writing `&var` returns a reference to `var`.

|

||||||

|

We can then assign to that reference:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

... or:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

We aren't actually assigning to `ref` here, we are assigning to the variable to which `ref` is a reference.

|

||||||

|

This works because the left side of an `=` doesn't have to be `&var`. As long as it returns a reference, we can assign to that reference:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

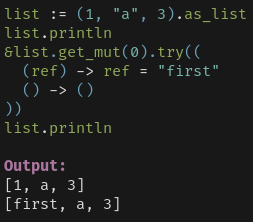

This is used, for example, by the `get_mut` function:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Here, we pass a reference to our list (`&list`) and the index `0` to `get_mut`.

|

||||||

|

`get_mut` then returns a `()/(&{Int/String})` - either nothing (if the index is out of bounds)

|

||||||

|

or a reference to an element of the list, an `Int/String`. If it is a reference, we can assign a new value to it, which changes the list.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## Multithreading

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

(...)

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

---

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Note: all of the pictures are screenshots of Alacritty after running `clear; mers pretty-print file main.mers && echo $'\e[1;35mOutput:\e[0m' && mers run file main.mers`.

|

||||||

|

|||||||

Reference in New Issue

Block a user